The Women Airforce Service Pilots

When the U.S. was drawn into World War II, many citizens wanted to do anything they could to support the effort. It would take enormous air power to defeat the enemy in Europe and in the Pacific, and young men were answering the call in droves. Those unable to serve in the military took up the work on the home front, and women were needed to step outside of their traditional roles to fulfill the demand. The world would never be the same as a new and empowered female culture emerged.

For the first time in history, it became socially acceptable for women to pursue work outside their homes and cast off social norms on behalf of the War effort. This employment gave women their own means of financial security and newfound freedom. They worked side by side with people of diverse backgrounds, learning about life outside of the constraints of the traditional role of wife and mother. The women who would become the Women Airforce Service Pilots saw another window of opportunity open up of this time of change, the chance to become military aircraft aviators, an idea that confounded both men and women of that era. They dared to forge a new path, and it would not be easy.

While the War was brewing abroad, female aviators Nancy Harkness Love and Jacqueline “Jackie” Cochran saw an impending need for women aviators to support the military if the U.S. was going to be drawn in to the conflict. They both forged their own campaigns for a female-led military pilot program for women, believing that any qualified American woman could learn to fly just as well as her male counterparts, and were needed to fly modern military aircraft to support the War efforts. However, military leaders felt that women lacked the strength and agility, even that they were “psychologically unfit” to fly such aircraft.

In 1941, most women stayed at home, tending households and caring for children. However, by the time America entered World War II, a new female workforce had emerged to become a cornerstone of the U.S. industry’s role as the primary supplier of equipment for the Allied war effort. Women were producing airplanes in mass quantities, symbolically depicted as “Rosie the Riveter”. These aircraft needed to be transported to U.S. airbases before being transported overseas to the frontlines but there was a shortage of pilots to carry out the task due to the large volume of male pilots being ordered to combat duty overseas.

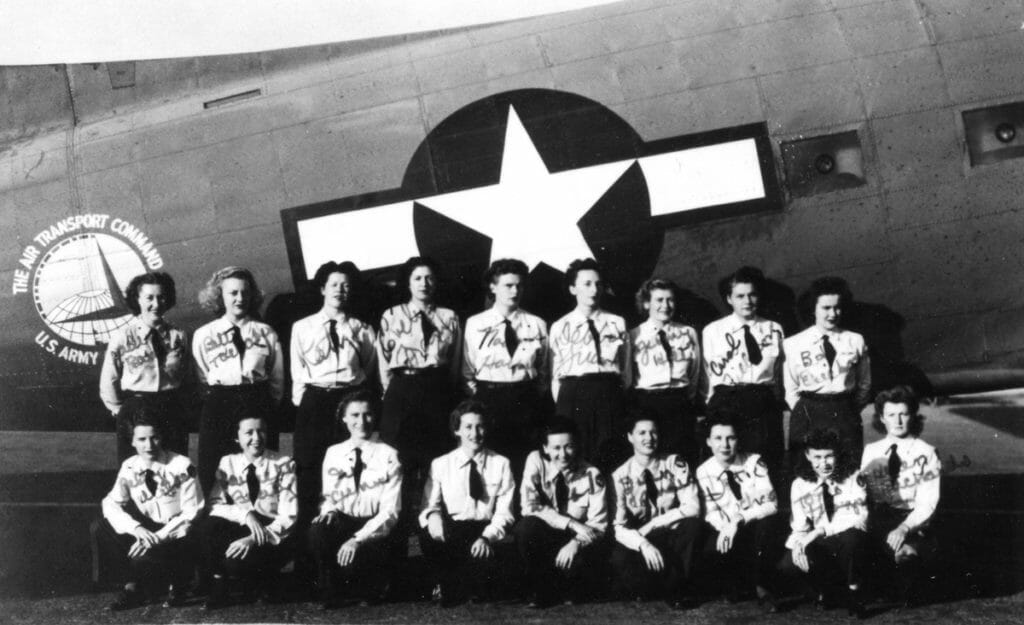

Facing this dire shortage of pilots at home, the Army relented and in 1942 decided to allow women an opportunity to prove that they were capable military pilots. By August of 1943, the Women Airforce Service Pilots was formally established. 25,000 women eager to serve, applied, but only 1,830 met the qualifications, which included holding a private pilot’s license, passing an Army physical, and meeting age, height and education requirements. While 1,074 women would earn their wings and become official WASP, they would face frequent opposition, knowing they were needed but frequently unwanted.

Classes of female cadets, based at the all-female Avenger Field in Sweetwater, TX, completed the same primary, basic and advanced training courses as male U.S. Army Air Corps cadets, regardless of their prior flight experience. They followed a strict military regimen; barracks were six to a room with one bathroom for 12 women. They marched everywhere, did calisthenics and ended their day with taps. They took part in infantry drills, barracks inspection and oaths of allegiance just like male cadets training elsewhere. The WASP held themselves to a high level of performance and behavior, determined to make their mark and prove their worth.

In order to free up as many male pilots as possible for combat, the WASP were scattered around the country at 126 air bases to perform many essential tasks and fly the more than 80 types of aircraft manufactured for the War, even the B-29 Superfortresses – the world’s most advanced bomber of its time. These skilled pilots performed essential non-combat military duties, including ferrying planes from factories to airports, towing airborne military targets in live-fire exercises, transporting cargo and test-flying new and repaired planes.

Because of the era’s attitude toward women and their lack of equal opportunities and treatment, the WASP were marginalized, regardless of their skill as aviators or willingness to serve their country. The circumstances of World War II gave them the chance to fly for their country stateside, but for decades they were left out of history books, not even recognized for their service. It would be 33 years before the WASP were granted military and veteran status.

Even though they believed they should be considered military personnel for the work they were doing, which was equal to male service pilots of the U.S. Army Air Corps, they were classified as civil service employees, with a promise that they might at some point officially join the Air Corps. But political opposition ensured that day never came during their service, and the group was disbanded in December 1944 without veteran benefits. Their records were classified and sealed from the public, locking their story away and concealing their contribution to the War effort.

Instead, the WASP paid their own way for the opportunity to serve their country. Determined and dedicated, the women paid for their own dress uniforms, transportation and room and board. 38 lost their lives in accidents while performing this service to their country, but because they were not military personnel, their families were billed for the transport of the bodies of the deceased. Often the WASP themselves would pool their meager resources to cover the costs when the families could not.

The WASP endured sabotage attempts, given dangerous assignments that male service pilots refused to do and berated for doing a “man’s work.” The opposition they met each step of the way was formidable, but their character and determination carried them through their service with dignity and success.

There is no mistaking the truth that the WASP paved the way for women in aviation. Modern women military aviators stand on the foundation created by these trailblazers. They had to fight tooth and nail for the chance to serve their country during World War II and in doing so joined women around the country who changed the landscape for generations to come.